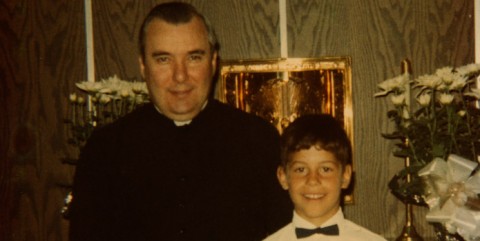

Just a couple of days into the Toronto International Film Festival this year, a curious commonality was noticeable in a number of the documentaries that I screened – re-enactments. While I only managed to see just under half of the nearly 50 documentary features in the TIFF line-up , it was surprising to see the storytelling approach — where significant past events are recreated via actors and, sometimes, animation — relatively widely employed. While some notable non-fiction films have made effective use of the practice — such as The Imposter or The Thin Blue Line — re-enactments more often feel in line with television productions of the Unsolved Mysteries variety. They remain a controversial element of documentary making, potentially challenging a film’s authenticity by introducing an outside, fictional element. It’s significant that the practice of re-enactment is the singular focus of one of the festival’s most-discussed docs, The Act of Killing , making this challenging film an appropriate place to begin. Director Joshua Oppenheimer, together with Christine Cynn and other anonymous co-directors, turn Indonesian gangsters into would-be Hollywood stars. The former death-squad leaders, responsible for the massacre of more than a million undesirables in 1965-1966, gleefully go along with Oppenheimer’s unusual plan, re-enacting the techniques they used to torture and murder suspected Communists, from off-the-cuff demonstrations of the cleanest way to strangle a victim to more elaborate set pieces involving interrogations and the destruction of a village. Verisimilitude is not the intent here. Although these over-the-top re-enactments push the limits of documentary ethics, they also shed light on the outsized personalities of the main subjects and reveal their histories and character. This conflation of a horrific reality with stylized fantasy also challenges the viewer and the perpetrators and becomes an unexpected form of therapy for the latter group. Mea Maxima Culpa: Silence in the House of God More literal examples of re-enactments are present in Alex Gibney’s Mea Maxima Culpa: Silence in the House of God , the prolific Oscar-winner’s exploration of child sexual abuse by Catholic priests. Focused around a Milwaukee priest who abused countless boys at the deaf school he ran, the film features the American Sign Language testimony of a number of men, spoken aloud by the likes of Ethan Hawke and John Slattery, but not distractingly so. Despite the forcefulness of the now-grown victims’ anger, expressed via their demonstrative signing and reinforced by the actors’ delivery (itself a form of re-enactment), Gibney decides to go one step further, recreating key sequences from their stories: silent scenes in which the priest prowls through the dorms ready to pounce on a sleeping young boy, or abuses the sanctity of the confessional booth. These sequences lack in subtlety and while they don’t undermine the strength of the film as a whole, they seem entirely superfluous. [ Editor’s Note: Gibney talks about his reasons for using these re-enactment sequences in an upcoming Movieline interview. ] Even more conventional is the use of re-enactments in Janet Tobias’ N o Place On Earth , the story of Ukrainian Jews who spent nearly a year and half living, literally, in caves to avoid capture during World War II. The majority of the film consists of actors portraying the circumstances of their flight from persecution and the conditions of their underground existence. Still-living survivors offer commentary in intermittent talking-head sequences, but the intended weight of the film is in the re-enactments which at times break from simply illustrating the story to feature actual scripted sequences. In the process, No Place on Earth ventures a step too far into docudrama. Given that the film is a production of the History Channel, it will likely connect with TV viewers, but, personally, scenes with the survivors re-visiting their cave sanctuary late in the film carried far more emotional resonance than the recreations.

See the original post:

Reacting to Re-Enactment: Which Toronto Documentaries Use The Controversial Technique Well − Which Don’t